Akhenaten, the pharaoh that ruled Egypt in 1300 BC and in his reign enforced the worshiping of one god - Aten "“ the sun disc is considered the first revolutionary in human history, but because of his radical views on religion his successors destroyed most physical evidence of his legacy, which today is more imaginative than monumental.

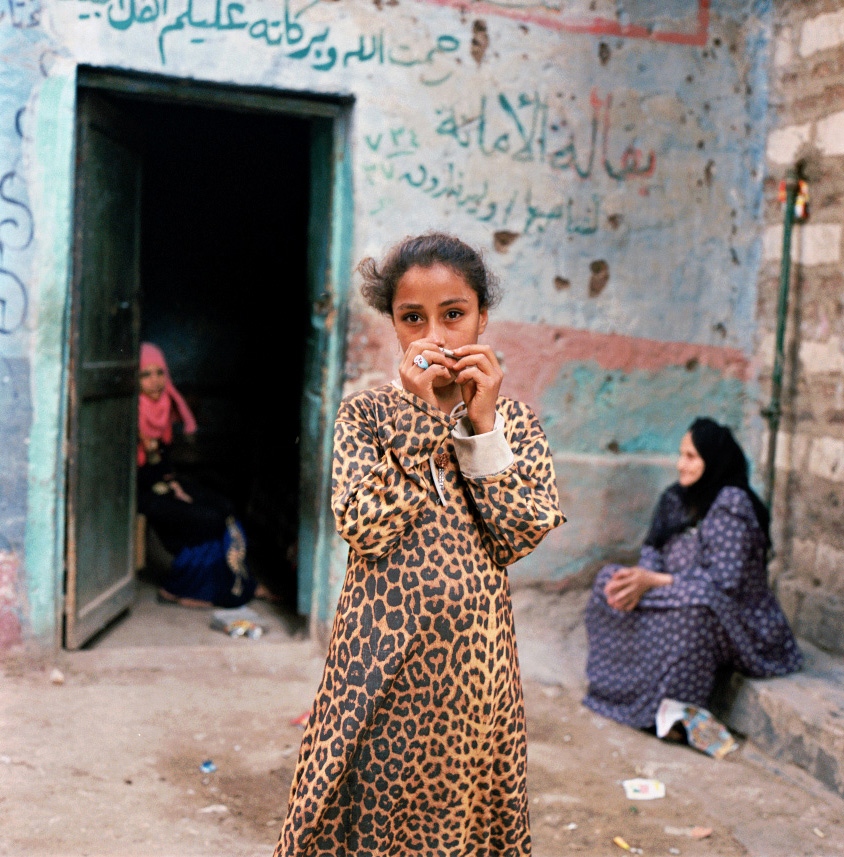

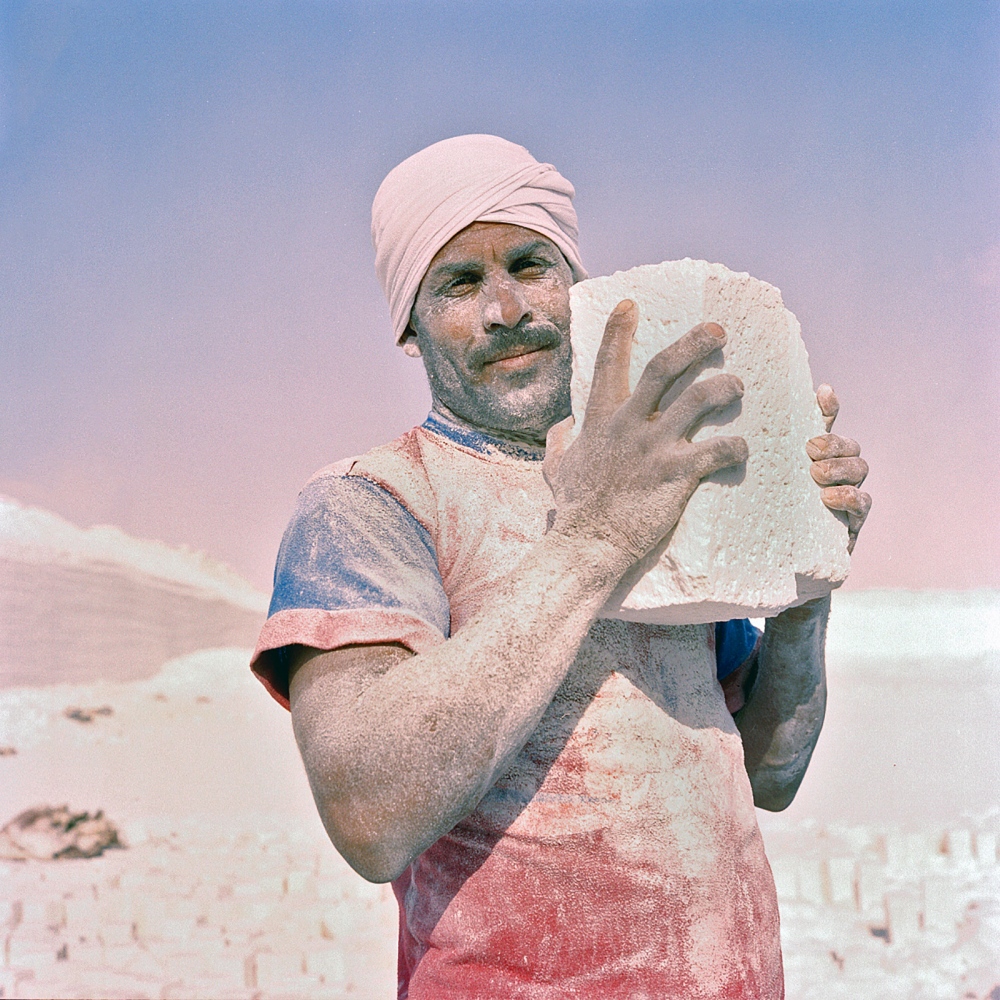

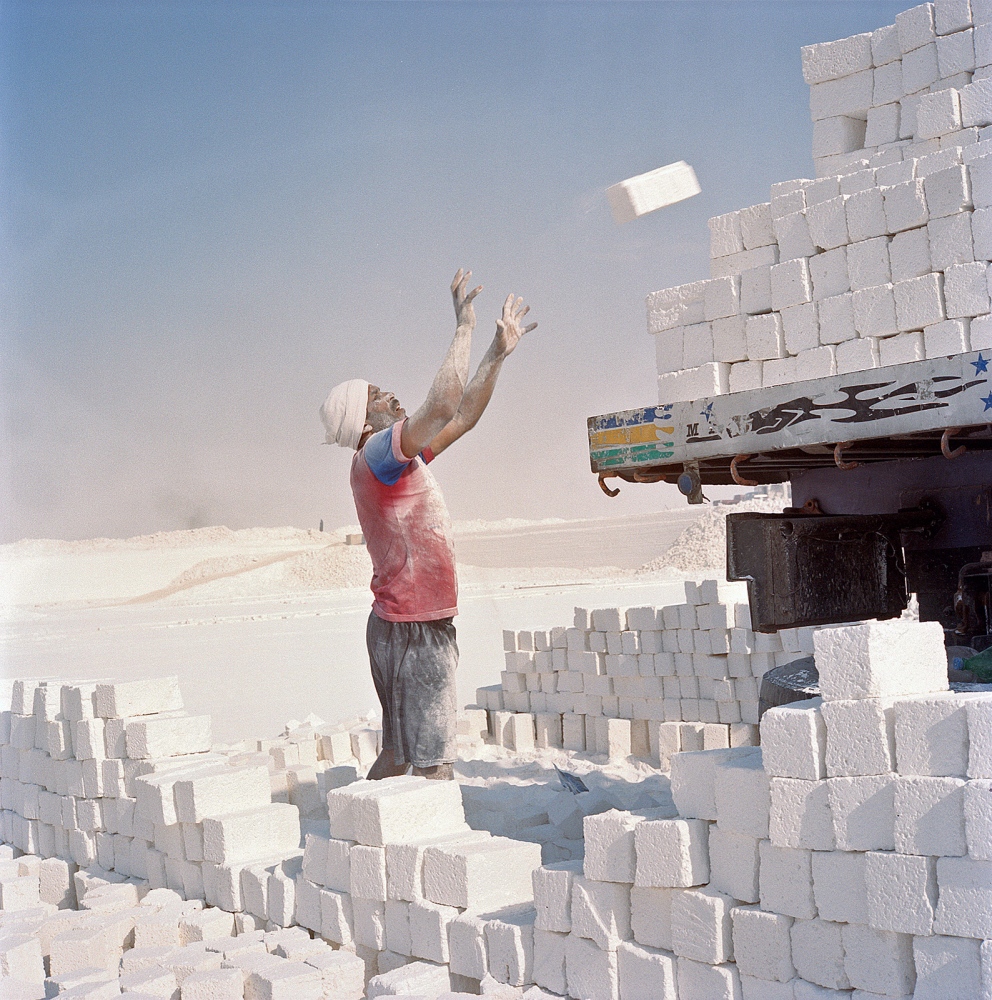

In order to establish new religious practices and fully abandon the old, Akhenaten built a new capital in the desert, about 36 miles south of Minya on the southern banks of the Nile. Akhetaten city was hastily constructed in mud-brick within an approximately 5-year period and covered an area of about 8 miles on the east bank of the Nile River. Within a few years, the previously unoccupied desert became home to Akhenaten's royal court and an estimated thirty thousand people followed him into the desert. The modern-day rural town of Tel-Amarna lies in immediate vicinity to Akhenaten's ancient city with the population mostly engaged in agriculture. Akhenaten was the father of Tutankhamun and the husband of Nefertiti, he had the power and vision to move thousands of people to an inhospitable place of no natural value. However, his city was abandoned shortly after his death, because of its desert location, where drinking water had to be brought in from the river.

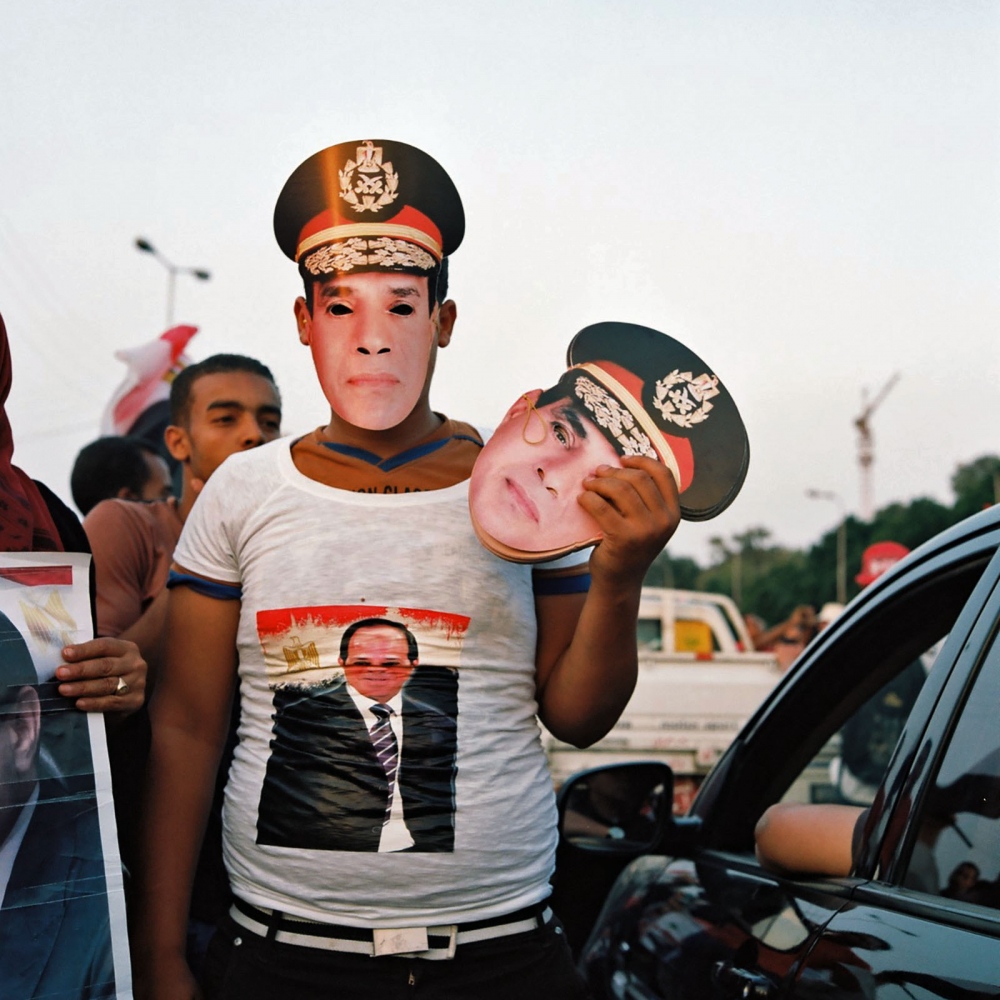

Despite of him being eviscerated from the Egyptian landscape over 3000 years ago, this project examines parallels between Akhenaten "“ the revolutionary, founder of monotheism and the modern day Egypt, especially in light of the country's most recent events and political changes. The ways in which Akhenaten and other great pharaohs of his dynasty expressed their power are often similar to what we see in the personality cult of today's Egypt. Much like in Akhenaten's era, his high-class subjects built shrines to the pharaoh in their homes and gardens, on the eve of the elections street vendors in Cairo put up large-scale posters of Sisi all over the city. The pharaohs were often depicted with their powerful forefathers. In a similar way, Sisi's profile was photo-montaged next to Egypt's previous rulers Nasser and Sadaat.